Our ability to recognize patterns is key to understanding how the world works. But we’re prone to see patterns that aren’t there. Sometimes a coincidence is just a coincidence.

Humans have an exceptional gift for recognizing patterns. We are a hypothesis-generating species. The regularities we observe in our world allow us to explain the past and to anticipate the future. We owe the scientific and technical achievements of human civilization largely to this ability to identify the causal relationships between disparate events.

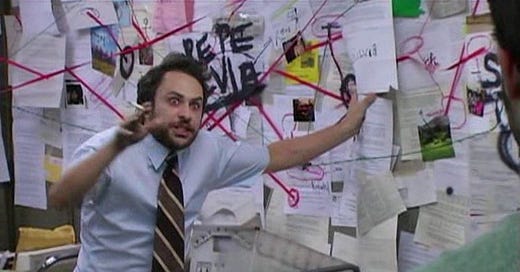

But we sometimes draw connections that aren’t there. We aren’t always good at recognizing genuine randomness—we tend to mistake uniformity for randomness—and are too ready to assume that two things that occur at the same time must be linked. The result is that we pick out patterns that aren’t meaningful in the sense they reflect any actual underlying relationship between things. In other words, we read too much into statistical noise. We see faces on the surface of Mars.

It’s not always easy to distinguish between meaningful signal and statistical noise. It’s reasonable, after all, to consider whether what looks like a face is actually a face. But we may be biased in favor of finding patterns and dramatically underestimate the probability that what looks like a face might just be produced by natural weathering or lighting conditions. The fact that certain rocks look like a face to us is at best weak evidence that they really are a face in some way that matters. In the absence of other compelling reasons to think the rocks are a face, the fact that they look like a face is probably a coincidence.

Some people are pretty bad at telling the difference between faces and shadows. But the reason certain people see occult faces is not that they’re necessarily stupid or ignorant of basic facts. On the contrary, it takes creative intelligence and detailed knowledge to pick out patterns—real or not—that others don’t see. Conspiracy theorists have some pretty stupid ideas, but they’ve often considered their subject more thoroughly than most people who correctly dismiss their theories. The reason most of us aren’t Flat Earthers is not that we’re more familiar with the evidence the Earth is round. The reason people draw implausible or unlikely connections is not because they’re fundamentally stupid but because they lack a specific epistemological skill in assessing evidence. As

writes, they’re not stupid so much as they are “bad at thinking.”Of course, the people who insist that “there are no coincidences” or that “everything happens for a reason” often do so for psychological or emotional reasons. They may prefer to find an explanation for events that gives them an illusion of understanding or control rather than concede that contingency plays a significant role in our lives; they may discount conventional or expert views out of a general distrust of authority or a desire to show they are sophisticated, independent thinkers; they may be looking for an ad hoc justification of something they want to believe or already believe; or they may be seeking to attribute things they don’t like to sinister outside forces.

But there are coincidences. Good forecasters, like good historians and good scientists, recognize the role that chance plays. I don’t know whether there is some metaphysical sense in which everything is connected—in which God or Fate determines the order of the universe—but I do know the idea that everything happens for an intelligible reason isn’t helpful in explaining things. It’s not that there are no obscure patterns and no hidden forces at work behind events. But while we shouldn’t categorically dismiss the possibility there are surprising connections between things, neither should we accept those connections are real without strong additional evidence.

Sorry I haven’t posted for a little while! I took some time facilitating forecasting at a synthetic biology workshop, which I hope to write about at some point in the future. In the meantime, I should have a new episode of Talking About the Future on the prospects for the war in Ukraine coming out soon. If you’d like to help me continue producing newsletters and podcasts, you can support me by buying a paid subscription and sharing this post with others.

You write, "Conspiracy theorists have some pretty stupid ideas, but they’ve often considered their subject more thoroughly than most people who correctly dismiss their theories."

I find it endlessly interesting, and very under discussed, how the UFO wackos with crazy hair were right all along, and the science clergy who dismissed them with a lazy wave of the hand were wrong.

LESSON: Be wary of experts, they typically have too much investment in the status quo to be truly objective.