The Parable of the Rocks

Dumb rules for forecasting

Scott Alexander wrote an interesting essay a few months ago about the value of “simple heuristics that almost always work.” These rules broadly consist of assuming that things that generally don’t happen, won’t happen. While rules like this may seem trivial or dumb—and shouldn’t be the last word—they’re actually a key to accurate forecasting. I’ll be off next week for personal reasons, but will return in two weeks.

One basic rule of forecasting is that things that rarely happen, rarely happen.

In February, Scott Alexander of Astral Codex Ten—who thinks a lot about forecasting—wrote about what he calls “heuristics that almost always work.” Alexander tells a series of stories about people in different roles—a security guard, a doctor, a futurist, a skeptic, a job interviewer, a volcanologist, and a weather forecaster—who all use some version of this in assessing situations. His futurist, for example, is always confident that hyped innovations or social movements won’t bring about radical change. His skeptic is equally confident that surprising contrarian ideas will turn out to be wrong. And both the futurist and the skeptic are almost always right.

People who assume rare events are unlikely to happen will generally be more accurate forecasters than people who occasionally predict rare events will happen. I think it’s reasonable to be skeptical of sudden, radical change or surprising, contrarian ideas. I’ve follow similar guidelines in my own forecasting. As a rule, for example, it’s safe to assume that projects will take longer than planned or that corrupt or incompetent leaders won’t be removed by coup. Another superforecaster told me years ago that one of his rules-of-thumb was always to bet that Russia is more expansionist than we think, which unfortunately still seems like a sound rule.

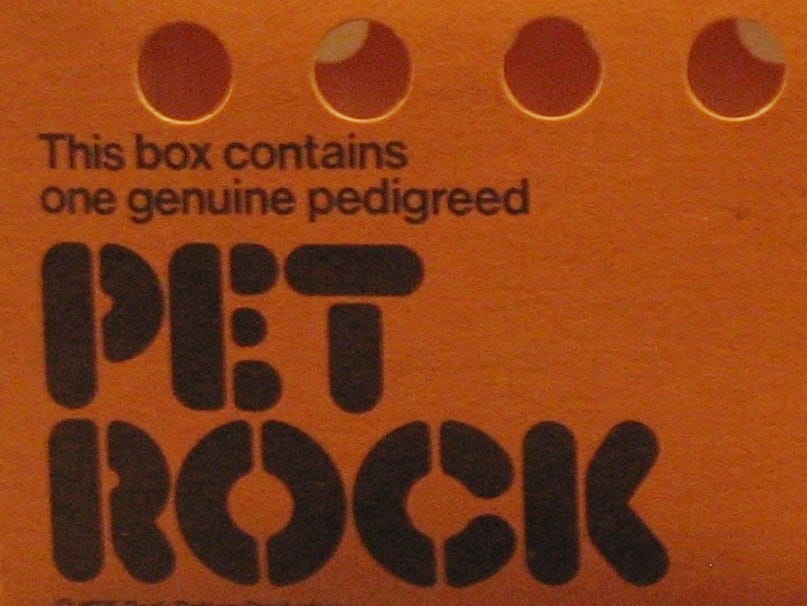

Some of these simple rules-of-thumb are had to beat. The problem is that the people who follow them don’t seem to be adding significant value or even really doing any meaningful forecasting. Each of them could be replaced by a rock with the heuristic they follow written on it. Alexander writes that the futurist’s rock might say “Nothing ever changes or is interesting,” while the skeptic’s rock might say “Your ridiculous-sounding contrarian idea is wrong.” The rocks don’t know anything about the specific situation in which they’re being consulted. What’s written on the rocks doesn’t change. But they’re right most of the time anyway.

You could, in other words, simply replace the people in Alexander’s story with their rocks. The rocks might even be preferable to the experts, since the rocks don’t pretend to represent anything more than a simple rule about how often things happen. The experts might pretend to have a specific reason for thinking a particular thing won’t happen, when all they’re actually saying is that things like it rarely do happen.

But this story doesn’t seem quite fair to the people in Alexander’s examples. The ability to apply base rates to real world situations—simply to realize that rare events are rare—is one of the hallmarks of a good forecaster. It’s not as easy to identify and follow useful heuristics as you might imagine. These rules-of-thumb may be the product of years of experience or of careful analysis. They may seem obvious in hindsight, but in fact not everyone is appropriately skeptical of radical change or surprising contrarian ideas. In practice, many people—even if they know the rule written on the rock—believe too readily that a specific situation is an exception to the rule.

Nevertheless, Alexander’s experts are wrong to act as if rare things will never happen. The reasonable futurist’s rock should say, “Things *rarely* change or are interesting”. The fair-minded skeptic’s rock should say, “Your ridiculous-sounding contrarian idea is *very probably* wrong.” We shouldn’t simply assume away the probability of rare tail events. Ideally—although in practice it may be extremely hard to do—we want to discriminate between the situations when an otherwise unusual thing will happen and the ones when it won’t happen. Rare, surprising events are often the ones we would most like to predict in advance. In some cases, where the greater danger is from failing to predict something than from wrongly predicting it, we may want to err on the side of overpredicting rare events. We should always make an effort to identify genuine exceptions to the rule.

But it still makes sense to start from the rule that things that rarely happen, rarely happen.

The US is about to join a handful of repressive autocracies in denying reproductive rights to women. The draft decision overturning Roe and Casey—and allowing states to force women to bear children against their will—lays the groundwork for a planned broader attack on bodily autonomy rights, including the rights to decide whom to marry, what kind of sex to have, and how to raise your children. It explicitly calls into question the constitutional basis of rights that weren’t firmly in place when the country was founded—a time when human beings were kept as slaves and women and sexual minorities were treated as second-class citizens.

Another good heuristic is to pay attention to Robert!