In this episode of my podcast Talking About the Future—recorded on Veterans Day—I talk with Director of the Transatlantic Program at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute in Ottawa and Superforecaster® Balkan Devlen about the future of NATO and European security. You can listen to our full conversation using the audio player above or on most podcast platforms. Excerpts from our conversation, edited for clarity, are below.

So let's start with the big, obvious question. What does the election of Donald Trump mean for NATO, and what does it mean for Ukraine? Trump says he can end the war in Ukraine in 24 hours. I saw Stephen Walt wrote in Foreign Policy, however, that Europe is screwed and Ukraine is really screwed. What do you think?

BD: I think that—maybe just to step back a little—I think Donald Trump's foreign policy style, his personal politics style, is one of high variance, in the sense that unpredictability—and this is nothing original here that I'm saying—but his unpredictability also suggests that the outcomes of his policies or the consequences of his policies are also high variance, in the sense that it can vary quite a bit between very positive values of that outcome for whatever the values you are highlighting versus it can go to very negative values as well. And I think that unpredictability is both an asset and a curse. It is an asset because it will force the other party sitting across the table from the US administration to think about whether this president who is mercurial and can change his mind rapidly and without necessarily consulting with many others, neither allies nor those who are in his administration, could shift and move in completely different directions. So it will make them think, in a way. That is not the case if you have a much more predictable foreign policy. Now, it could work, as I said, in a very positive way or in a very negative way. Whether the sum of that high variance ends up being in the net a positive expected value or a negative expected value is, I think, the question.

When you look at NATO, I think a lot of the NATO allies and partners such as Ukraine are looking at the incoming Trump administration and trying to identify what is the transaction that we can engage in with this administration that will turn this high variance into positive expected value for us versus what do we need to avoid doing that would create a negative value for us? And here I have two issues. One is that Macron recently talked about how Europe needs to actually take care of European security and cannot and should not rely on the will of the American people. My question is, of course, why did you wait? It should have been the case, anyway, right? But, you know, better late than never.

So I think there is scrambling in some parts of Europe to try to figure this out. I would say that this was as a result of wishful thinking, as well as a very legitimate criticism of Europe from Trump’s advisors, saying that if the war in Ukraine, Russia's invasion, is an existential threat to European security, why are you not doing more? Why are you not spending more? Why are you not ramping up production? Why are you not contributing more? Why are you not also putting your money where your mouth is?....

With World War II long in the distance and the Cold War over, I think a lot of people don't see the value in collective security. So I guess my question to you is, what is its value? Make the case, if there is a good one, for collective security and for the value of NATO in whatever world we're in right now.

BD: I think the value is very clear. This is not charity. This is about self-interest. It is a lot cheaper, both in terms of treasure and blood, if you can avoid war. To avoid war, when you're dealing with aggressive, revanchist powers, such as Russia, or those who think that their status and the respect and the prestige that they are receiving in the international system is not commensurate with their actual power, such as China, which individually can take on individual NATO member states because of the difference in size, it is a lot cheaper for the western states to band together and confront these revanchist and revisionist powers and deter them from further aggression....

It's going to cost less because war is more expensive than deterrence. And of course, there is the sacrifice of blood. We are talking today on Remembrance Day here in Canada—it's Veterans Day, I think, in the United States—that commemorates those who fought in the world wars and made the ultimate sacrifice. So it is a lot cheaper, both human cost and treasure wise, if you band together and deter. And if you cannot deter, it's a lot easier to protect your sovereignty and your prosperity and your security if you can fight together....

Let's talk about nuclear blackmail. You and I are both interested in existential risk. If NATO, in one way or another, say by creating a red line and sending an invitation to Ukraine to join, gets into a more direct conflict with Russia, I think there are legitimate concerns about nuclear war. But, also, there's a real moral hazard if Putin can leverage those concerns into getting his way. How seriously should we be concerned about nuclear war and Putin's saber-rattling and what can we do about the moral hazard issue?....

BD: When we do the forecast and we look at the base rates, one of the things with nuclear war is we’ve never had a nuclear war. We had nuclear bombs dropped, but we didn't have a nuclear war.... So we don't have much of a base rate to go with, but we can think about the background rate. What is the existing situation and how that can change conditional on X, Y, and Z happening. At this stage, I don't see conditions on the ground that would make me update my background risk significantly.

Are you saying that you don't think the background risk is higher now when there's a conflict in Ukraine than it was in 2021 when there was—still a frozen conflict in Ukraine, but a colder conflict?

BD: I don't think it is higher in a meaningful sense that I can differentiate. The reason is that that background rate is low. I don't think we went from 1% chance a year for a nuclear war to 10%.

Sure. We went from low to slightly higher low.

BD: Exactly. And that generally comes with huge error bands, right? Because, again, we have no real base rate for this. This is very much almost vibes in terms of what the background rate is.... So let's assume it's 1%—one of the numbers that went around for a nuclear exchange between Russia and the United States.

Terrifyingly high in some ways.

BD: Terrifyingly high, but I could say that maybe as a result, it went up, I don't know, to 1.3%. Maybe I'm wrong and it’s 2%.

A 30% increase in the risk of a bad thing seems bad.

BD: Yes, but overall risk is 1% to 2% even if it is a 100% increase. Is that a decision-making point that will justify the other costs of not taking action?....

Can Ukraine win a war of attrition? They've expanded the draft, right? They're running out of manpower on some level. There are a lot more people in Russia. Now Russia is sending North Koreans to fight in Kursk. It seems like they have a deeper well of people to draw on, even if they're losing more of them.

BD: Yes. But, first, I don't think the well is bottomless.... They're not sending conscripts yet, which would have a significant domestic psychological impact and also an economic impact. The economy can continue to run a little bit more, but I don't think they can sustain this more than 18-24 months at the same level....

We should not forget that when you take the United States and Japan and others, we're talking about a $50+ trillion economy, 20 times the size of Russia. We can outproduce them. Are we willing to do that? No. It is a political will issue on the part of the West that we don't want to put our money where our mouth is. We’re trying to confront an adversary, we’re trying to conduct a war with peacetime means....

Objectively speaking, Europe by itself should be able to outproduce and outgun the Russians. The fact is, they don't want to do it. We here in Canada don't want to do it. And people complain in the US about what is basically a rounding error in the defense budget being sent to Ukraine. So it really comes down to the political will and the mindset that we are in wartime....

There is a pathway, but the pathway goes through our willingness to step up and change our mindset and actually show that we can collectively outproduce, outgun Russia in this war. Unfortunately, I don't see that happening. In essence, I'm pessimistic. I don't see that political will coming. What I'm seeing is completely the opposite. The delusion that if we throw Ukraine under the bus, we can freeze the conflict, and then it can go away, and then we can go back to business as usual.

Here on Remembrance Day, maybe we should remember why we fought in the past.

BD: Absolutely.

You can listen to my earlier conversation with Superforecasters Jean-Pierre Beugoms and Scott Eastman about the war in Ukraine here. This newsletter depends entirely on reader support, so if you’d like me to do more interviews like this, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. You can also support me by sharing this post, as well as rating Talking About the Future on your favorite podcast platform.

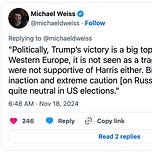

![November 18, 2024 tweet by Michael Weiss reading, "'Politically, Trump’s victory is a big topic, but unlike in Western Europe, it is not seen as a tragedy in UA. They were not supportive of Harris either. Biden-Sullivan’s inaction and extreme caution [on Russia] left Ukrainians quite neutral in US elections.'" November 18, 2024 tweet by Michael Weiss reading, "'Politically, Trump’s victory is a big topic, but unlike in Western Europe, it is not seen as a tragedy in UA. They were not supportive of Harris either. Biden-Sullivan’s inaction and extreme caution [on Russia] left Ukrainians quite neutral in US elections.'"](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!LGVx!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F1ee9de62-9aef-485f-8751-7948f607805b_882x558.png)

Share this post