Fingers Crossed for a Soft Landing

Do you believe in immaculate disinflation?

The Fed has been raising rates in order to bring inflation down from the forty-year high it reached in 2022. That could trigger a recession—and we should expect output to fall and unemployment to rise in 2024—but because the economy still has room to slow it’s unlikely to be severe.

The Federal Reserve has spent the last year trying to slow the US economy. The whole point of raising interest rates is to discourage spending by increasing the cost of borrowing money. When money is tighter, it’s harder for businesses to raise prices and for workers to demand higher wages. This also disrupts a potential “wage-price spiral” since businesses and workers feel less need to raise prices or demand higher wages when they don’t anticipate having to pay higher prices and higher wages themselves. But there’s a risk that by slowing the economy the Fed could trigger a painful recession. That would not only hurt a lot of Americans financially, but could also determine whether Donald Trump returns to the presidency. The Fed doesn’t want to cause a recession if it can avoid it—it would prefer if possible to lower inflation without reducing how much we produce and earn—but slowing economic activity is the most effective way to fulfill its mandate by bringing inflation down.

The real question is not whether the US economy will slow, but how much it will slow. In theory, it might be possible to bring inflation down without the economy going into recession—to achieve what economists call a “soft landing”—but it has been difficult to do in practice. A recent paper found no precedent for a central bank like the Fed dramatically reducing inflation without “substantial economic sacrifice or a recession.”1 The three times the Fed raised rates at least 5 percentage points before were closely followed by recessions. The closest thing to an exception to this pattern is when the Fed raised rates 3 percentage points in the mid-90s without causing a recession. But that was a significantly smaller rate hike and in response to just 3% inflation. Even if this recent round of interest rate hikes doesn’t cause a recession, we should expect growth to slow and unemployment to rise.

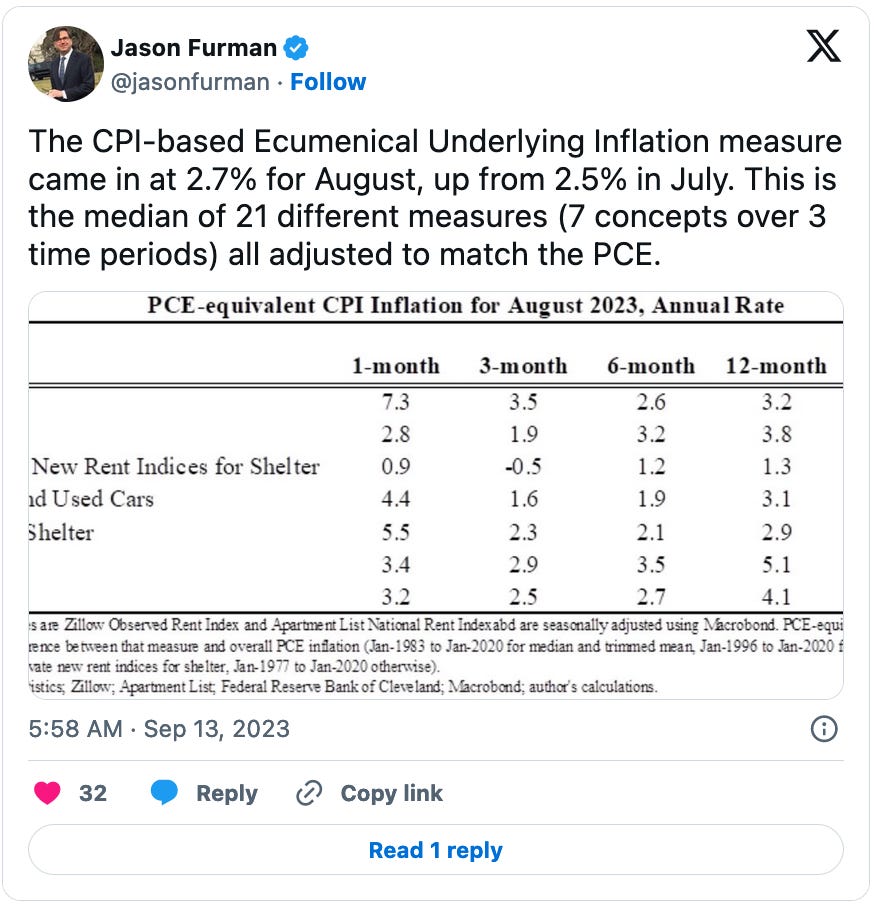

But there’s more reason for optimism than that history might suggest. The recent forty-year high in inflation was largely thanks to a once-in-a-generation pair of temporary supply shocks in the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Inflation has already come down dramatically from 9% last year as the impact of those shocks has faded. It remains too high for comfort—and the last mile of inflation reduction is likely to be the hardest—but the underlying rate of inflation after stripping out variable factors may be close to 3% now. In other words, we may not be that far from the Fed’s official target rate of 2% already. That’s likely to continue to fall over the next year as the interest rate increases work their way through the economy, even if the Fed doesn’t raise rates any further. The fact that the Fed didn’t raise the interest rate in September suggests it’s adopting a wait-and-see strategy and will raise rates further only if inflation doesn’t seem to come down.

The issue now may be whether the Fed has already overshot by raising rates too high. Because interest rate hikes can continue to affect economic activity well after they’re implemented—although macroeconomists are divided on how much lag we should expect from these hikes—we should probably expect the economy to slow for a while. The Fed has raised rates rapidly—more than 5 percentage points since March 2022—to a level that is likely to be fairly contractionary. But at just 3.8%, the unemployment rate remains close to the lowest it has been in decades, which means that spending can probably continue to slow without putting a lot of Americans out of work.

That certainly doesn’t mean the US economy is out of the woods. There’s probably about a 15% chance of a recession in the US in an ordinary year. The rapid interest rate increases likely mean that the chance of a recession is a lot higher than it would be in an average year. The Fed could decide to do another round of hikes if inflation doesn’t continue to slow significantly. Another crisis—an extended government shutdown, an acrimonious labor dispute with car makers, or a sharp increase in oil prices—could make the economy hard to manage. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said that after the last Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting that while there’s “a path to a soft landing,” whether we manage one “may be decided by factors that are outside of our control.”

More than half of the economists surveyed in the latest FT-Booth US Macroeconomists Survey expect a recession to begin before 2025, but three-quarters think unemployment will stay under 5.5% over the next three years. Metaculus forecasters estimate there’s a 40% chance of recession starting before 2025. The median FOMC member forecast is 4.1% unemployment in the fourth quarter of 2024. My best guess is that the US economy will slow and unemployment is likely to increase in 2024. Inflation won’t come all the way down to 2% before the end of 2024, but the Fed probably won’t raise rates much further than it already has. If there is a recession, it’s likely to be mild, and it won’t start early enough or be severe enough to have a major impact on the 2024 presidential election.

My Forecasts

45% chance of a recession in the US starting before the end of 2024

78% chance unemployment in the US will be under 5.0% at the end of 2024

You can see all my recent predictions on Fatebook here.

Help me get to 100 paid subscribers! Buying a paid subscription allows me to devote my time forecasting and writing consistently. I wouldn’t read too much into the astounding ABC News/Washington Post poll that found Trump is leading Biden by 9 points in a head-to-head matchup. Polls this far ahead of a general election aren’t particularly meaningful, and—while it’s certainly possible Trump could win—I’m confident he won’t win the national vote by 9 points. If you enjoyed this post but aren’t ready to buy a paid subscription, you can support my work by sharing it with others.

Great analysis Robert! I hope you’re right that, if there are mildly deteriorating economic conditions, they won’t play that much of a role in the elections. Your take seems very reasonable, but I’ll still probably lose sleep over every negative economic indicator.