Today I’m launching a new podcast, Talking About the Future. My first guest is Swift Centre Director and superforecaster . The Swift Centre—which I forecast with—seeks to produce forecasts that help decision makers address real-world problems. You can listen to my full conversation with Michael using the audio player above. Excerpts from our discussion, edited for clarity, are below.

I want to start by talking briefly about Russia, since Russia has been in the news the last couple of years. Years ago, in another podcast interview we did, you told me you had a trick for forecasting what Russia would do. Could you tell us what that trick was?

MS: My heuristic for forecasting Russia back in those days—and I think it's stuck with me ever since—is when my fellow forecasters might assign a probability to Russia doing something where they would be pretty assertive, or they would take some kind of aggressive stance, I would just up that by 10% and that worked out pretty well for me.

I'd say, well, I think you've got pretty good fundamental analysis, but there's one piece of the puzzle here, which is a willingness to have a more aggressive posture on their part and I think that you're underestimating it. And if you think there's a consistent bias among the people around you, then you can actually save yourself a lot of time by saying, okay, well if I think you're always off—if I think you're generally you're generally in the right direction, but you're off by a bit in this one specific way—then you can pick up some accuracy points by correcting what you see as that bias.

So that was my rule of thumb back in those days, and I think that's remained the case. Although I think the alpha in that has gone now. I think everybody sees more clearly that Russia is a bit more assertive than people thought they were maybe in the 90s…

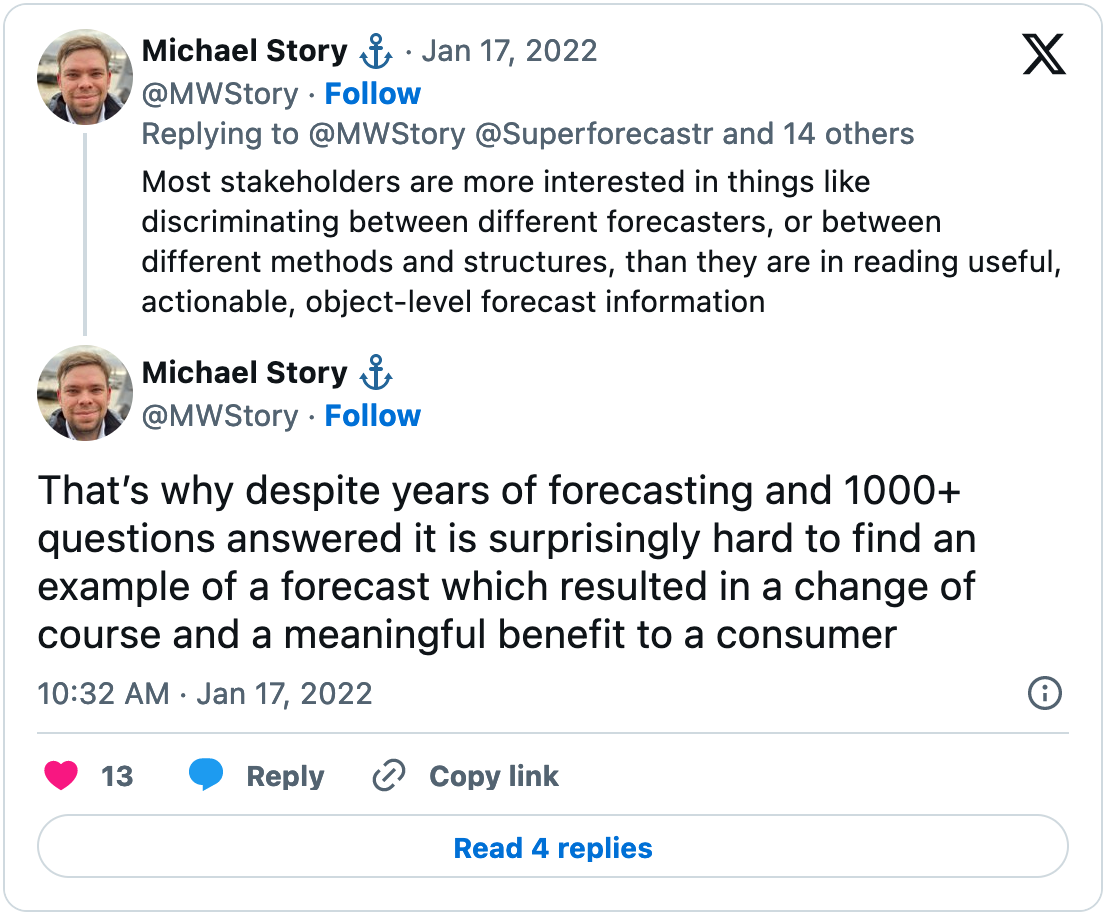

I understand the idea for the Swift Centre sort of grew out of an observation that you made initially on Twitter, that it's hard to find an example of a forecast that "resulted in a change of course or a meaningful benefit to a consumer." Why do you think that is?

MS: Why do I think that we haven't had the impact that we could?

Yeah, that forecasting hasn't had the impact that it could.

MS: So I do believe that. Yeah, I think that we—you and I, I mean, personally—and we as a community of forecasting researchers and practitioners and whatever, we've not had as much impact as we could. But I should qualify that by saying that we're starting from a low base, and you have to get a lot of basic research out of the way first to kind of to get to that point. So I don't think we've been wasting our time, but I think that a lot of the things we've been doing have been fleshing out the basics and getting to a point where we can start to have more impact....

For a given set of questions, we know a lot about how to answer these things accurately. And, of course, as we know selecting the right kind of people with the right kind of psychology, and giving them training and support in particular ways, and structuring them in teams, and then using an aggregation algorithm to pull in their forecast by recency or whatever—or whether you use a market or something like that that does that for you—we know a lot about how to do that and kind of get rid of sorts of bias and problems and whatever.

So that's great. But that's actually not a problem that anybody has in real life. I mean, maybe some people do, but that doesn't correspond that closely to the type of problems that decision makers deal with. Decision makers are quite unlikely to have a list of things that they're worried about and just need to assign probabilities to, right? That's not the problem they have. Very frequently, they don't have a list. They have a vague sense of concern about X country....

When you think about a really valuable forecast, it's often in the form of a warning, like, hey, here's something you didn't think about, but we think that this is a high risk. If you have a model where I'm waiting for you to tell me the stuff you're worried about, and I put a probability on it, that doesn't happen, right? So there's a lot of circumstances where we've got very good at figuring out who's a good forecaster, but that doesn't necessarily mean that we're producing information that's valuable for making decisions.

So the original Good Judgment Project in some ways was optimized for finding out who's a good forecaster, for producing forecasting research, but not really for helping decision makers. If we have the capacity to make good forecasts, how can we leverage that capacity to improve their decisions and help them?

MS: Yeah, so I think there's a few things we can do. And this is what Swift Centre is about. So if you wanted to take all of that fantastic research that exists on how to better answer a set of forecaster questions, and then say, okay, how do we make sure that we're answering the right questions to help a decision maker? We can't just—I think that's the essence of the tweet story, right?—it's like we're firing these forecasts out into the void and saying, here you go, here's what we think. But I feel like that's suboptimal. You need to hug very close to decision makers and need to understand the range of options they have and that kind of thing, and get really close to try and figure out what we think is helpful....

One thing with the Swift Centre you've emphasized is trying to make forecasting a profitable product, wanting to produce something that people will be willing to pay for. Why do you think that's important?

MS: Well, I think if we're not able to produce information that people value more than it costs to produce, what are we doing? To me, that's such an important factor.

I think—and I say this with love as a member of the forecasting community for a long time—but I think there can be a sense in our community of resting on laurels, of being a little bit willing to blame everybody else for not getting what we're trying to do. That's true of every subculture and community, but I think there's a little element here where we are trying to—sometimes you will read responsible people say, well, institutions are hostile to forecasting and probabilities, because probabilities make people uncomfortable, or it feels like gambling, or an instinctive kind of disgust reaction to thinking about things probabilistically. And that's all true, right? That is all true. I agree, that can happen, and that can be a barrier.

But it's not true everywhere, and institutions that have tried to adopt forecasting have often not stuck with it. And the fact that they tried to do it I feel like is a sign against there being an issue with them culturally not wanting to do it. They've tried to do it so they're clearly not in that group of people that have a kind of cultural problem with forecasting, but they've still found it wanting in some way.

I think when you look at that you have to think about, well, why is that? Well they're spending some money, they're spending some time on things, they're obviously not getting enough value from the information to justify the expense. I think that if you can reduce the cost of forecasting to the point where you do feel confident that you can get information that's valuable—because I guess that’s the thing, if we research ways to do this that are highly accurate, but it's so expensive that it's better for the decision maker to not use that information because the cost of getting it is so high, then we're wasting our time, right? So I think being able to do things cheaply is incredibly important....

So let's talk a little bit about prediction markets. One thing that's often suggested is that instead of getting skilled forecasters and paying them to produce a bunch of forecasts, you can just set up a prediction market or set up a market on an existing prediction platform, and get a bunch of people to bet on whatever your question is, and then that's your forecast. Are prediction markets a viable alternative to the kind of forecasting that Swift Centre does?

MS: Yeah, all of these different structures, they're all trying to do the same thing, right? They're all trying to get a bunch of smart people and aggregate their views in a way that is more accurate than any one person could do. So a survey of forecasters, a prediction market they're all doing that in a different way....

What a lot of people will say is, well, you know, here's a dispute, we can just have a market. Let's just open a market on X and people can bet and then we get a market price, and that's the probability. And that sounds great. And you go, oh, that sounds perfect—that's free. I can get my information for free. That's what you're really saying, right? I want to get some information about how likely X is, and I get this for free.

But of course, it's not free! Why would people be in your market? They have to get compensated somehow. That's basically the core of the problem.... You want information, but the people participating in your market are not there to try to produce information for you. They’re there to do something else. So you end up with this mismatching problem....

Something you hear a lot in American circles is, if prediction markets were legal, all of these things would be different. People would be in markets all the time, it would be super easy to set up a market, everybody would be doing it. But in the UK, prediction markets are legal, and you don't see any of that really. And the reason is that the overhead costs are quite substantial, and the demand to participate in them is pretty small. One of the biggest sites in the UK for gambling is Betfair Exchange. If you go on Betfair Exchange, you can find markets on lots of unusual things, but they're very, very thinly traded. There's not a lot of people on there. There’s not a huge amount of demand to do this. People might go on there and bet trivial amounts of money for a bit of fun, but really there’s not a big thriving market there for people to participate in. And that’s not because it’s illegal. It’s perfectly legal. It’s all fine. It’s just that it’s not that attractive....

People that have run corporate prediction markets, if you talk to them, they nearly always tell the same story, which is, you can get lots of people to be in your prediction market for fun—and you're not paying them—but not for the things that you care about. So, if you're running a company you care about, are we going to close this deal, what's our next quarter going to look like—these are the things that you really want to know about. Here's a merger that we're proposing. We're going to buy this company. Is it going to happen? What price are we going to end up paying for this? All this kind of stuff. You open a market on that, they're just dead. Nobody cares. No one wants to participate in that because it's not fun....

One last question, Michael. In your official opinion as director of the Swift Centre, what's the best Taylor Swift song?

MS: Marriage Story. What’s it called? Love Story, that's what I meant. Love Story. That's the best Taylor Swift song. Love it.

For the record, I think all of Taylor Swift’s songs are fantastic—please like and subscribe, Swifties. The intro music to Talking About the Future is “Catch It” by Yrii Semchyshyn. If you enjoyed this post and would like me to do more podcasts, let me know in the comments or by liking this post. As always, you can also support Telling the Future by sharing this post with your friends and colleagues.

Share this post