Will Russia Invade Ukraine?

If we act like we're going to war, we're probably going to war

Will Russia invade Ukraine? We need to take the possibility seriously simply because all sides are taking the possibility seriously. Russia has an incentive to use its leverage to reshape the security architecture of Europe now. Russia wants credible commitments that NATO and Ukraine can’t easily make. If no agreement can be reached, Russia may decide that the only way to expel NATO from Ukraine is with military force, even though doing so will likely strengthen NATO’s opposition to Russian aggression.

This is the first issue of my new newsletter, Telling the Future. I’m not really ready to launch—I still have so much more to prepare!—but I have thoughts on the Ukraine crisis that I want to share while they still matter. More issues of the newsletter will follow soon.

Russia appears to be marching to war with Ukraine. Both Russia and NATO are going through all the motions of readying for war, even as Russia dismisses concerns as “hysteria”. Russian forces appear to be prepared for something like a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. There’s clear precedent for aggressive Russian action against Ukraine in the 2014 annexation of Crimea. But a full-scale invasion of Ukraine would be a new level of aggression. The closest comparison might be the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia—if Czechoslovakia had been an ally of the US at the time.

War appears likely now, if only because Russia and the US are treating it as likely. A lot of the factors that seemed important when I began making this forecast a few days ago no longer seem relevant now that events are in motion. Simply mobilizing troops on this scale increases the risk of war, because of the threat they pose to other countries. When military forces are on high alert, accidents and misunderstandings can lead to a war neither side would choose in advance.

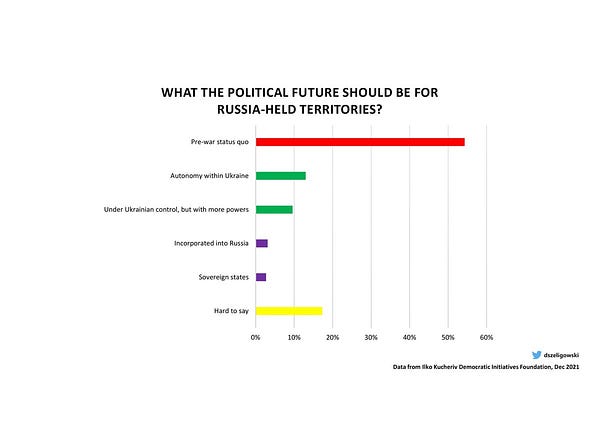

There doesn’t seem much room for a negotiated agreement between the various parties. NATO’s commitment to self-determination and democracy pose a fundamental threat to Vladimir Putin’s legitimacy and authority. Russia broadly wants to reshape the post-Cold-War security architecture of Europe by weakening NATO and by increasing Russia’s influence over its “near abroad”—former Soviet Republics like Ukraine. In particular, Russia would like

1. to ensure NATO won’t influence Ukrainian politics

2. to replace the Ukrainian government with a government friendly to Russia

3. to implement the 2015 Minsk II agreement on Russian terms

Russia may reasonably believe its window to act is now because its leverage will only decrease in the future.

These demands will be difficult for NATO and Ukraine to satisfy. NATO can’t easily assure Russia it will stay out of Ukraine because it’s committed to the principle that Ukraine has a right to decide for itself whether to join NATO. Withdrawing support for Ukraine in response to threats would also make NATO members like Poland and Romania question NATO’s commitment to defend them. NATO likewise can’t easily accept the overthrow of a democratically-elected government for a Russian client regime with little popular support. Simply implementing the Minsk II agreement on terms acceptable to Russia would be difficult because it would drastically undermine Ukrainian sovereignty and weaken the Ukrainian government. Russia may therefore conclude the only way it can achieve its goals is by force.

Russia has mobilized enough forces to conduct a full-scale invasion. But it seems to me that if Russia does attack it will most likely be a relatively quick strike to topple the Ukrainian government and cripple the Ukrainian military. It might partition or annex parts of Eastern Ukraine, but Russia presumably does not want to be responsible for the problems that come with governing Ukraine. Capturing and holding a country the size of the US eastern seaboard—that has a population of 47 million people—is expensive and would require an enormous commitment of resources. When the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia—which at the time had a population of just 14 million—it did it with twice the number of troops Russia has mobilized around Ukraine.

Even a more limited strike would be a vivid reminder to European countries of the value of NATO. Russia may actually have already overplayed its hand from this perspective. While Russia’s initial threats divided NATO members against one another, the threat of a broader invasion seems to have unified NATO in opposition to Russian aggression. Russia may nevertheless calculate that sanctions are likely to cause more damage to the US and Europe than they do to Russia. Expelling NATO from Ukraine may be worth the cost to Russia in any case.

Putin might still decide not to invade. It’s hard to forecast events that depend on the psychology of a single individual or group of individuals. It is clear Ukraine is a symbolic, emotional issue for many Russians. But I’m always skeptical of arguments that Putin is irrational or poorly advised. All leaders have their biases and blind spots, but it’s easy for forecasters to project our own biases onto another actor’s psychology. I think Putin may be making a mistake, but I don’t see much reason to believe he isn’t a canny, rational actor.

Negotiations will continue up to the last minute. I think the chance of war is high simply on the basis of how far along the path to war we’ve already gone. There may no longer be any off-ramp concessions that would allow Putin to back down gracefully. I think a full-scale invasion of Ukraine is unlikely since it would be a risky, elective gamble. But once a war starts it’s hard to say where it will lead. As of last night, the Good Judgment superforecaster aggregate forecast—which I contribute to—was that there’s a 51% chance NATO members accuse Russia of invading by May 31. Metaculus forecasters currently give Russia a 62% chance of invading Ukraine in 2022 and a 25% chance of entering Kiev in 2022.

My Forecasts:

• 65% Russia invades Ukraine before April 1

• 25% Russia occupies territory or cities outside Eastern Ukraine before April 1

Thanks to superforecasters Balkan Devlen and Scott Eastman discussing this with me. Balkan’s analysis of the Ukraine crisis is here and here. You can find other related forecasts using Nuño Sempere’s Metaforecast search engine. If you enjoyed this post, please do me a favor by clicking the like button and sharing the post with others.

> The closest comparison might be the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia

It’s not as unprecedented as you make it sound. In 2008 Russia invaded Georgia, marched their tanks all the way to their capital, then proceeded to annex 30% of the country.

Can you explain a 40% drop? Seems high. I understand the general concept of escalation / pull back cycles as a way to "farm" resources; historically Russia (and even North Korea) does this often. However, it does seem like there might be a regime change here given the physical troop movement, which is a fairly costly signal (both in resources and international attention) to make these negotiations work, unless there was some good reason that *this* is the time for a costly display of escalation.