In this episode of Talking About the Future, I talk with Forecasting Research Institute (FRI) CEO Josh Rosenberg about their research, including new results from the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (XPT) and the ForecastBench project on AI forecasting. You can listen to our full, in-depth conversation using the audio player above or on most podcast platforms. Excerpts from our conversation, edited for clarity, are below. If you enjoy our conversation, please share it with others!

So, Josh, how do we make forecasting useful to decision makers?

JR: This is really one of the core things that the Forecasting Research Institute was founded to do. I'm really excited about forecasting as a field. I've been following it for a long time. I think a lot of folks are excited about it. There still is this big gap where it seems like it's not being taken up as much by important decision makers as it could be. Some of what we're doing at the Forecasting Research Institute is focusing on some of the most difficult cutting-edge topics to apply forecasting to. So, for example, we recently released a project on AI-enabled bio-risk, whether AI will help amateurs synthesize bioweapons, which would increase the risk of a human-caused epidemic. We basically conduct expert panel surveys where we collect forecasts and views from a wide number of experts on the topic, and we get them to forecast the risk of a human-caused epidemic, the risk conditional on different advances in AI, and the risk conditional on implementing different policies. I'd love to get more into this, but that combination of tools, I think is going to be very helpful for closing the gap between the current states of forecasting, where it can be really helpful to get forecasts on a wide variety of interesting questions, but really making sure you're asking the right questions, having the right set of people answering them, getting high quality reasons for the forecasts, I think, is going to really help close the gap between forecasting and usefulness in decision making....

There was a prediction in the biorisk study that if AI was able to pass the Virology Capabilities Test it would be dangerous. Then OpenAI's o3 model did pass the test.

JR: That's right. And this is something that we've seen across our research, including in the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (XPT). It does seem that both superforecasters and domain experts underestimate the pace of AI progress, particularly on benchmarks. In this study, we asked people to predict the median year by which AI would surpass a team of human experts at this virology troubleshooting questionnaire. It basically asks questions about—you're running into a problem in your virology experiment, maybe the sorts of problems that would be related to synthesizing dangerous pathogens, and you want to ask an expert, how do I deal with this problem? This group SecureBio that created the benchmark got in groups of experts to actually answer a multiple-choice questionnaire and compared that to AI's results on this benchmark. What they found was in the middle of this year models like o3 did surpass that benchmark. Superforecasters and domain experts forecast median years of 2030-2034 for that benchmark to be passed.

So it blew past that really quickly. We've seen that with a number of AI benchmarks. It seems like you could have two interpretations of that. One is that forecasters—and maybe particularly superforecasters who are anchored to base rates of normal times—tend to underestimate AI progress. Another way you could interpret it is to say, well, this has been an unusually fast surge of AI progress, and we don't know it’s going to continue. Maybe this is just statistical variation. But it does seem like it's been a pattern for quite a few years. I remember superforecasters weren’t collectively super optimistic about AI beating humans in go, and then it happened really fast. I guess it's an open question whether we’re systematically too pessimistic or whether we're in a period of rapid AI progress that won't continue.

JR: Yeah, I agree that's a key question. I agree that one of the plausible interpretations is just that people are really underestimating AI progress and we really need to be paying a lot more attention because it's moving faster than people expect. An interpretation in the other direction would be to say, yeah, people are underestimating progress on these AI benchmarks, but it may be in part because the benchmarks aren't quite as meaningful as we thought when we designed them. So perhaps it does well on grad-student-level multiple-choice exams across a wide variety of topics. And we thought, oh, well, if you're doing that, you're probably able to make new scientific discoveries and things of that nature. But it actually just turns out that maybe the benchmarks are a little bit less connected to world capabilities. That’s another argument that I've seen. We're interested in digging into these topics and having a closer link in our forecasting questions between benchmarks and world impacts, so we're going to try to better understand what's actually going on there....

Another study you have that deals with rare events is the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament (XPT). This is something that you initially did a few years ago, and now you have something new coming out that follows up on those results. Can you tell us, first of all, what the initial study was and what we learned from it?

JR: Yeah. This was the largest forecasting tournament conducted so far on these topics of global catastrophic risk. We were looking at topics like nuclear war risk, pandemics, AI, and climate change. We had 89 domain experts and 80 superforecasters provide forecasts on short, medium, and long time horizons. Part of the unusual nature of the study is that we had forecasts 2-3 years out, 10 years out, 30 years out, and longer, so we could start to look at the relationships between forecasts at many different points in time. We collected forecasts on a variety of short-term indicators in each of the causes that I mentioned, and also, long term, what was the probability of these various causes leading to the extinction of humanity or to a catastrophic event, which we defined as at least 10% of the human population dying within a 5-year period. So very extreme, intense societal events. We were looking at some of the biggest potential risks and trying to get high-quality forecasts from domain experts and superforecasters on them....

So you have a new follow-up on the XPT. One of the things that I found really interesting was you looked at the accuracy of different groups and you found that the accurate group didn't necessarily all have the same opinions on the future risks.

JR: Some of the hope with the Existential Risk Persuasion Tournament was, there's these big disagreements about, for example, the likelihood that AI or nuclear war or pandemics could lead to catastrophic risks or the extinction of humanity. One logical thing you could do is say, let's get everyone to forecast near-term events related to each of those topics. Then let's listen to the people who are more accurate on the near-term forecasts about their long run forecasts. You know, if you think that short-run forecasting accuracy is correlated with more accurate beliefs about long-run risks, then that seems like a reasonable thing to put some amount of weight on. Unfortunately—or, I mean, it is what it is—it seems that there was not any meaningful relationship between accuracy on short-run forecasts and long-run risks. There just wasn't a clear pattern there. So we can't simply say, the people who are much more skeptical of long run risks, they're more accurate, so that's an update in their favor or vice versa. It just didn't seem like there's any clear relationship there....

So let's talk about ForecastBench. FRI tracks the performance of various large language models (LLMs) against human forecasters. A competition like this is particularly interesting from a forecasting research perspective, I think, because when you're trying to predict the future, the results aren't known to anyone, so AI can't train on the results in advance. There's no data leakage issue. They can't teach to the test the way they might with other kinds of benchmarks. So it's a hard test for AI. I've been pretty skeptical of the ability of current-generation AI—barring some new breakthrough, which of course is pretty likely—to compete with the best forecasters. Every time I write that, one or two of my readers politely tells me I'm going to look foolish pretty soon and that we’re about to be beaten by the AI. What are we seeing on ForecastBench?

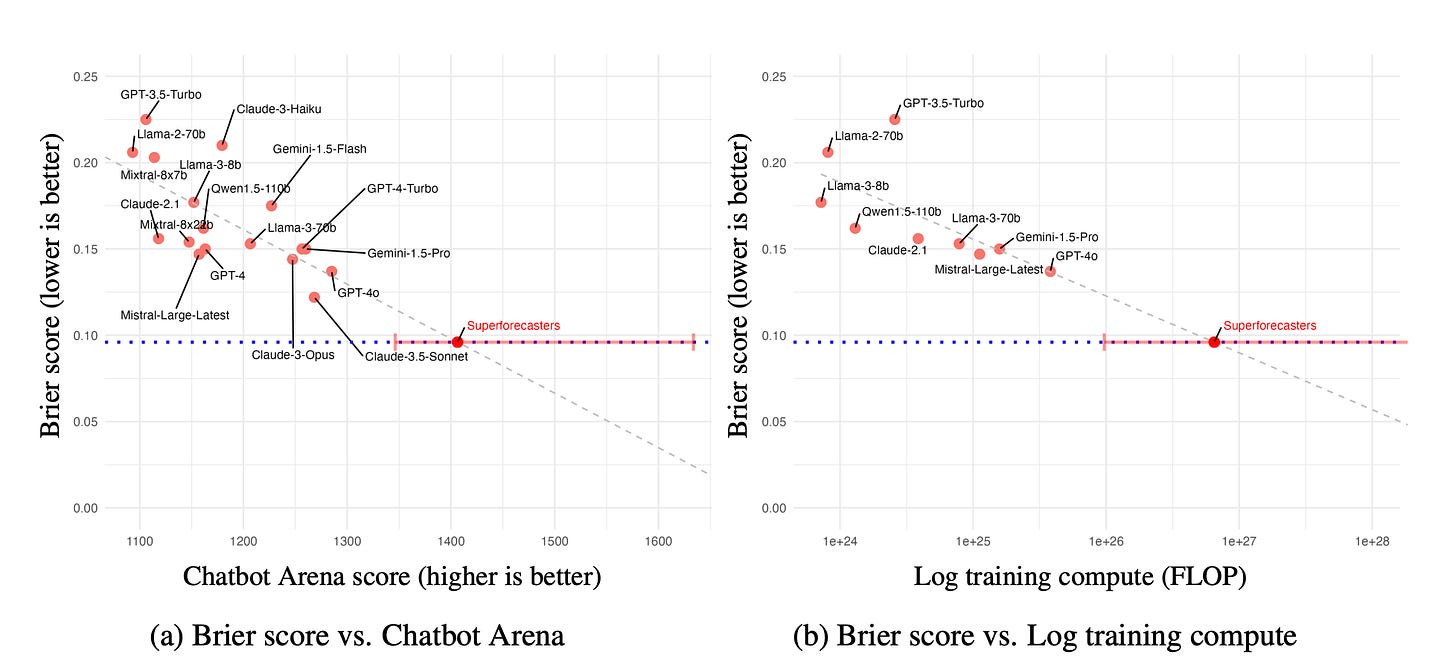

JR: So we are seeing gradual improvement of AI models on forecasting. These are our latest results. We're still in the process of finalizing them. The final numbers may shift a little bit, but I think the broad results should hold. We found that previously it seemed that, for example, the median of a group of humans that are drawn from the broader public on survey platforms, their median forecasts were beating the top AI models that had existed the last time we ran this. But, in this latest update, we saw that the newest top models, for example, GPT-4.5, were doing better than the median of the public. They still are meaningfully short of the forecasting accuracy of superforecasters. But for models released between 2023 and 2025, we do see gradual improvement on forecasting accuracy over time. If you extrapolate that trend, it does seem that AI will continue to improve, and may eventually catch up to the superforecasters....

Thank you for listening to Talking About the Future! Related episodes include “Michael Story on Making Useful Forecasts” and “Tom Liptay on Scoring Forecasts.” I depend on reader support, so if you enjoyed this conversation and want to encourage me to make more episodes like this please consider becoming a paid subscriber to Telling the Future. If you enjoyed this, you can also help others discover it by clicking the heart button at the bottom.