In this episode of Talking About the Future, I talk to Our World in Data global health researcher Saloni Dattani about life expectancy. Dr. Dattani recently wrote a wonderful article about life expectancy on her own substack . She is also an editor at Works in Progress. We talk about why life expectancy has increased, whether it’s likely to continue increasing, why the US lags behind other wealthy countries, the impact of semaglutide, why women tend to live longer than men, lifespan inequality, and the potential of advanced market commitments to accelerate the development of new technologies. You can listen to my full conversation with Dr. Dattani on the audio player above or on most podcast platforms. Excerpts from our conversation, edited for clarity, are below.

Let's start with a basic question. What is life expectancy and how is it measured?

SD: Life expectancy is a very counterintuitive concept. So I think a lot of people when they hear the term think that it means how many years they're going to live. Surprisingly, it doesn't mean that even though it's called “life expectancy.”

What it actually is is a metric that summarizes death rates across different age groups in one particular year, so if you think of the death rates across age groups in 2022, for example. What life expectancy tells you is the average lifespan of a hypothetical group of people who had the same death rates at different ages of their lives as the death rates we see in age groups in that year. So someone who is born in 2022, the life expectancy at birth in France, for example, is 82 years. What that means is that the average person who is born in France in 2022, if they face the exact same death rates as all the age groups did in 2022, they would live 82 years. So it assumes that, for example, a baby born in 2022 would face the same death rates when they’re 30 as the 30-year-old did in 2022, and the same death rates at 50 years old as the 50-year-olds did in 2022.

We're trying to assume that everything that we see in one particular year is the same as what people will experience in the future. That's quite a strong assumption. We don't actually know what people are going to experience in the future. We don't know if they'll face exactly the same rates of death as people do today. There could be new medical advances. There could be wars or pandemics. There could be various changes that we can't expect and we can't forecast very well, and those can all affect how many years the average person lives.

So you say it's quite a strong assumption. I would say it's obviously wrong. I think what you're talking about is “period life expectancy,” but you could also measure “cohort life expectancy,” which would be the actual life expectancy of someone born in my year. Those two measures have actually diverged, right? They diverged sometime around the end of I think the 19th century, and they no longer match up. We at this point would not expect them to be the same in the future. Which is to say we would expect someone born in 2024—unless there's some kind of catastrophe that affects global health—to live longer than the current life expectancy this year.

SD: Yeah, exactly.

So the divergence is quite large. The last year for which we have data is 1930. That's the last year for which we know the average lifespans of people who were born then, because almost the entire birth cohort has died by now. But in order to find out what the cohort life expectancy is for more recent birth cohorts you would have to wait until that whole birth cohort had died until we could find out what the average lifespan was. So if you look at the data from 1930, for example, the difference between period life expectancy at birth and cohort life expectancy is about 12 years, which is quite large. So we can expect there to still be a divergence even now. It's hard to say how big that divergence is, but it's definitely the case that there will be one.

One other reason that that is the case is because even the death rates that we see right now are not just about the current conditions that we live in. They're also about past conditions that people have faced. So, for example, people who are 80 or 90 years old now, they have developed various health conditions in the past that affect their health now and that affect their death rates now. And so, if these health conditions are declining or death rates are declining in general, then we won't expect to see people born today to face the same death rates as 90-year-olds today....

One really interesting thing about that is that reducing child mortality really increases life expectancy. Can you explain why that is?

SD: Yeah, so in the past child mortality was overwhelmingly the driver of gains in life expectancy. So imagine you have this 15% risk of dying in your first year of life. If you manage to drive that down—if 15% of the population or so manages to survive past that first year, which is the deadliest they'll face in their lifetimes—you manage to then increase the average lifespan quite significantly. So it's this initial period that is very deadly to infants. Once they get to childhood, the risks of death decline enormously. This used to have an outsized effect on average life expectancy in the past. Now that child mortality is at much lower levels than they were in the past, further declines don't matter as much in terms of the average lifespan.

It’s as if the first year or first few years of your life was like a gauntlet you had to get through, and if you pass through that filter, potentially you could live a long time.

SD: I also looked at some of the data on not just the first year, but also the first week and the first day of life. And the first day of life is probably the most dangerous day of your entire lifespan. In the US, there's data on mortality rates per day for infants. What you see is that there's a power law distribution between the number of days of your life in the first year versus your risk of death. So in the first day of life, about 1-in-500 infants in the US die that day. But by the end of the year, just counting all the infants who have died by the end of the year, that’s 1-in-200, which is just over two and a half times as many. So the majority of that risk in infancy is concentrated in the first day and the first few weeks of life, which is also quite surprising. But essentially what that means is that the risk declines enormously....

There's this gap in life expectancy between men and women. Are there biological factors related to gender that are also part of the issue?

SD: Yeah, that's right. Maybe I could start with trying to explain what this gap is and where it comes from. If you look globally, the sex gap in life expectancy is about five years. Women have a life expectancy about five years higher than men's. But that varies a lot between different countries, and what's also really interesting is that it varies a lot over time.

The sex gap in life expectancy now is much shorter than it was in the 1980s and 90s, and one of the main reasons for that was smoking. So smoking increased the risks of lung cancer, but also a range of other cancers and also cardiovascular diseases. Because it became so prevalent over the 20th century, especially among men, that widened the gap in life expectancy between men and women. There are also various other reasons that there is this gap. It's not just smoking. Smoking was a major contributor but the reason that there’s a gap in life expectancy actually comes from differences across the lifespan. Even if you look at infancy, even actually on the first day of birth, there is a much higher risk of dying among newborn boys than girls,

What are the boys dying of?

SD: It's not extremely clear why that is. There are various theories around it. One of them is that because boys have one X chromosome rather than two, they're at a disadvantage at trying to protect themselves against various infectious diseases. The X chromosome has genes that are related to immune function. Because boys only have one, they're less protected. Another sort of effect of that is that they're more vulnerable to malnutrition and various diseases related to that. So, even at this very young age, you see a higher death rate in boys.

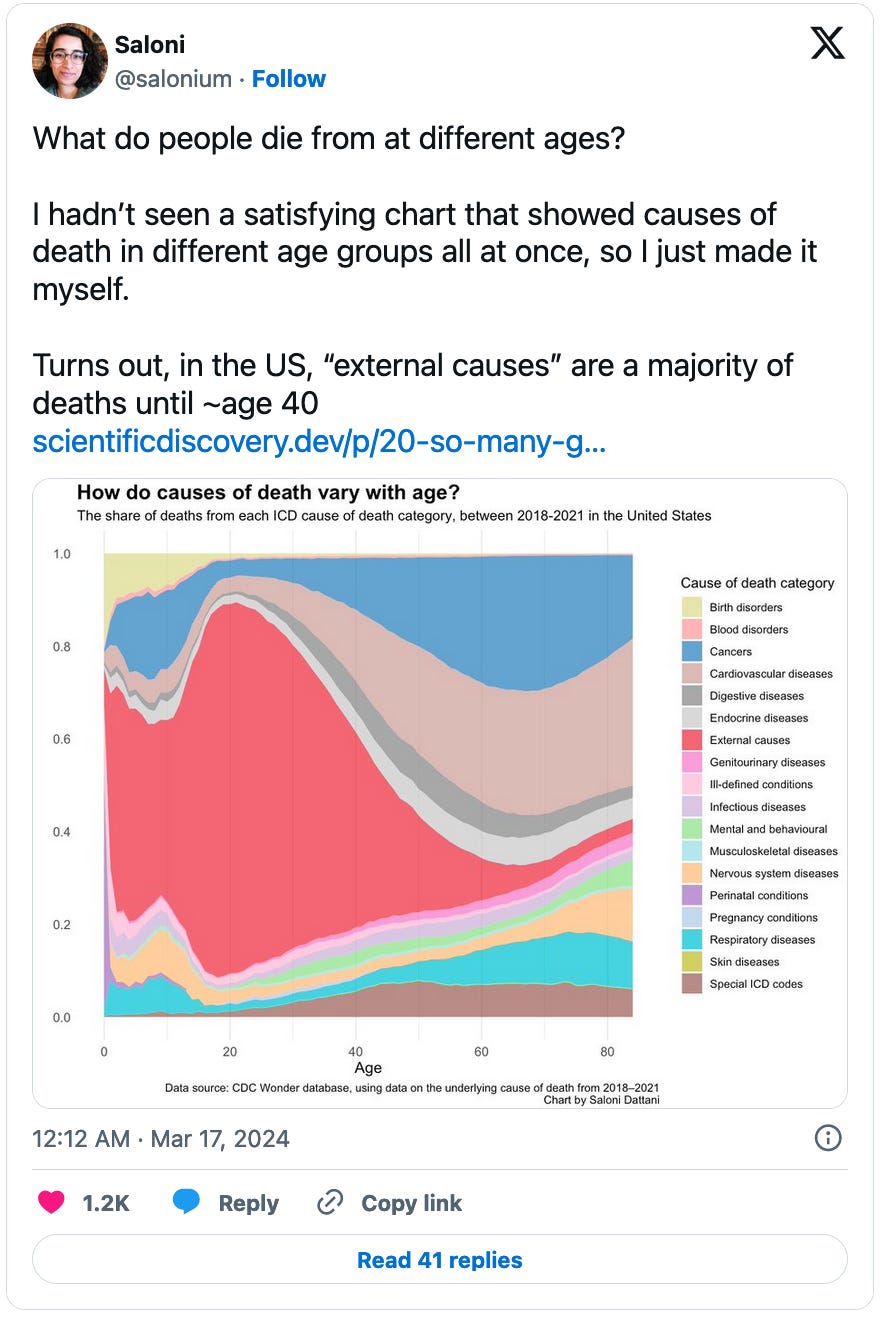

Then you see that continuing on in childhood and adolescence, and that’s usually for different reasons. There’s also this still higher risk of diseases, but you also see things like violence, accidents, overdoses, and things like that that widen the gap in adolescence. Then various other risk factors start to play a role. This could include occupational risks, so things on the job, taking riskier careers, and then there are various other health-related behaviors, alcohol consumption, drug use, smoking. All of these factors can be dangerous in themselves but can also lead to other diseases that can lead to long-term health consequences across someone's life. Those have all played a role in making this gap in life expectancy.

That's also not a universal. There are some countries that until recently had a higher life expectancy in men than women. This includes I think some South Asian countries and a few West African and North African countries. Those tended to have higher risks of death in newborn girls because of things like female infanticide, but also because of childhood neglect and various social and cultural issues like that....

Is there any evidence that the maximum lifespan of a human is changing particularly that you know of?

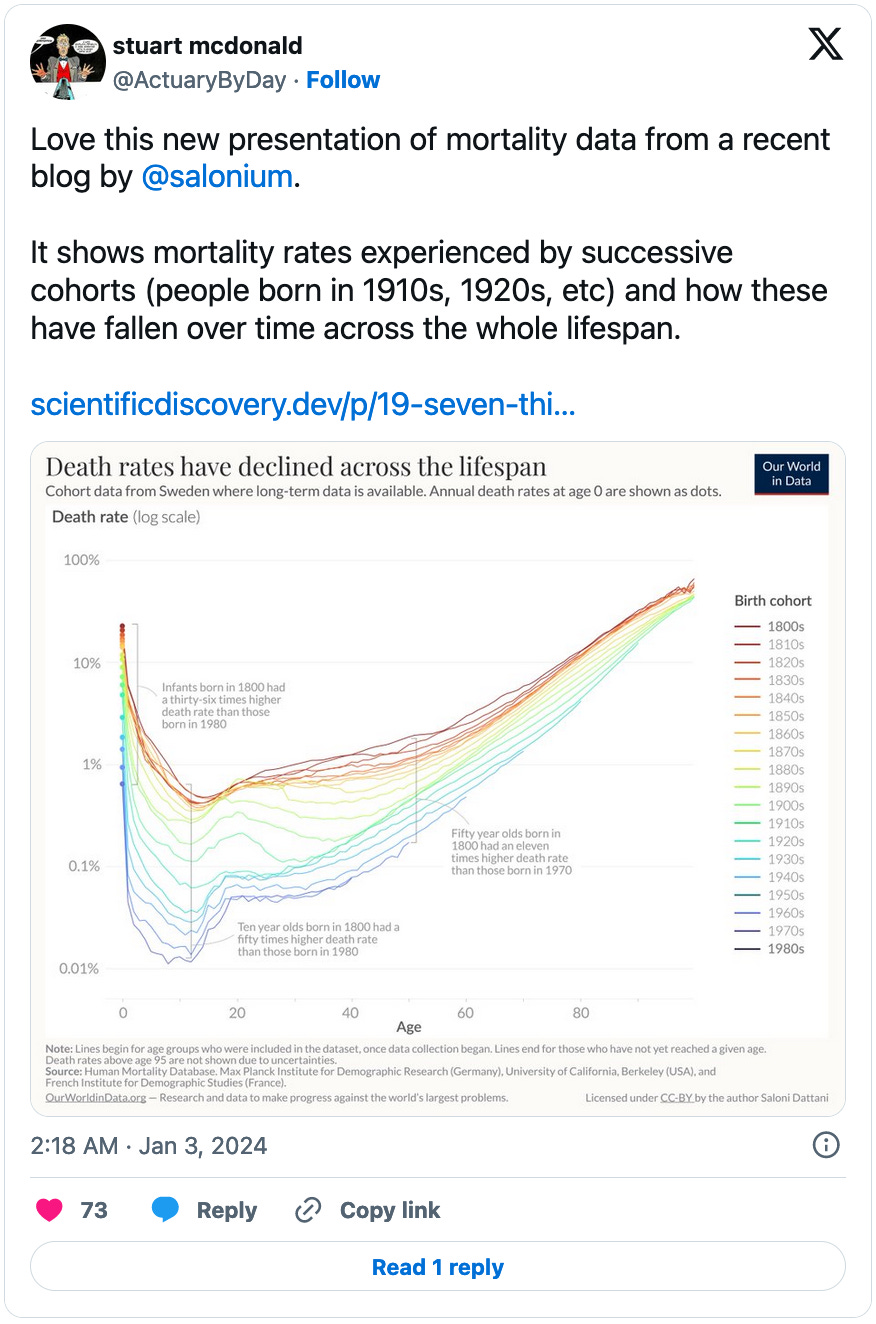

SD: Yeah, I don't know about this. What I usually think about when I'm trying to figure this out is the risks of death across the lifespan. If you plot, for example, the risks of death from age zero to a hundred on a chart, you'll see this j-shaped curve. Infants have a higher risk of death, and then it declines suddenly in childhood, and then it starts to grow suddenly in adolescence, and then it grows exponentially throughout adulthood. And what you see over time is that this whole curve has moved downwards, so at every age of our lives we have lower risks of dying than the generations before us. This is what you would see even on a log scale, even if we're talking about declines of like 10 or 50 times at different ages. And you see this entire curve shifting downwards, and that makes me think that the maximum lifespans could be much longer than people think. It's not the case that they level off. The risks of death don't massively increase at some older age. They increase exponentially at a steady rate, and they've all been moving downwards....

You can find previous episodes of Talking About the Future here. If you found this interesting, I also recommend Dr. Dattani’s new Substack post covering related topics and her article on why we didn’t get a malaria vaccine sooner in Works in Progress. If you’d like me to make more podcasts like this, you can support my work by buying a paid subscription to Telling the Future.

Share this post