The American Crisis

Minnesota No ICE

The Trump administration is treating Americans like subjects in its attempt to consolidate authoritarian power.

The imperial boomerang is coming back around to us. The idea of the “imperial boomerang”—which comes from Aimé Césaire’s Discourse on Colonialism—is that empires eventually use the same repressive techniques they use against their colonies against their own citizens. Césaire argued that Europeans shouldn’t have been surprised at the rise of Nazism, when they had already accepted treating non-European people with the same brutality. With Nazism, Europeans were simply experiencing firsthand the practice of colonial rule. “Before they were its victims,” he wrote, “they were its accomplices.”1

The US has been a relatively benevolent world power—“relatively” is a key qualification—but we have now largely cancelled the policies and programs that valued the humanity of others on the grounds that those policies and programs don’t serve our immediate interests. We’ve discarded the liberal international order we created for a short-sighted, rapacious realism. We’ve seized Venezuela’s oil—while leaving the illegitimate Chavista regime largely in place—without much justification beyond wanting that oil for ourselves. We tried to strong-arm our own ally into giving up Greenland—to which we already have broad access—because the president says we need “Complete and Total Control” of the Danish territory. While the Trump administration seems to genuinely believe these moves serve our national interest, they seem to be at least in part demonstrations that we can take what we want without having to consider the rights of others.

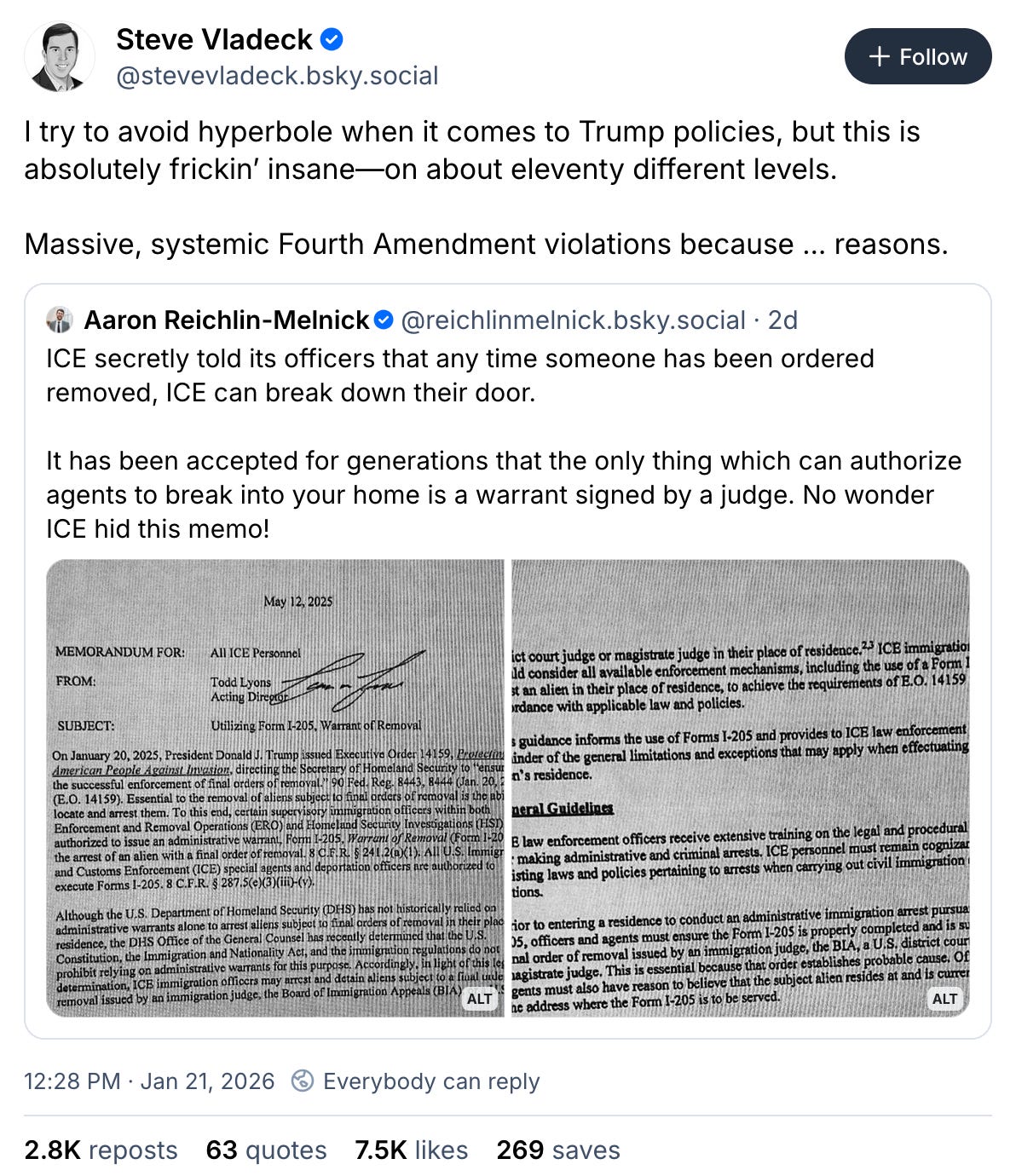

The contempt we show for others doesn’t start at the water’s edge. The doctrine that “the strong do what they can” has no obvious limits. Once we accept it’s okay to disregard the interests of others—that there’s no need to treat others the way we’d want to be treated ourselves—there’s no compelling reason to act any differently toward our fellow citizens and neighbors. We shouldn’t be surprised when a state that glories in being an unaccountable hegemon sends people to inhumane foreign concentration camps without due process; when it forcibly enters homes and arrests people without a judicial warrant; when it shoots people in their cars; when it dismisses people who are observing or protesting as “domestic terrorists”; or when it effectively occupies a major city. These manufactured confrontations aren’t meant to make us safer. They’re a deliberate show of force intended to show us we have to comply without question, to show us that even American citizens are subject to the government’s arbitrary authority.

Robert F. Worth, “Welcome to the American Winter” (The Atlantic)

“One of those latecomers was a 46-year-old documentary filmmaker named Chad Knutson. On the morning after Good was killed, he was at home with his two hound dogs, watching a live feed from the Whipple Building, where ICE is based, a five-minute drive from his house. A protester had laid a rose on a makeshift memorial to Good. As Knutson watched, an ICE agent took the rose, put it in his lapel, and then mockingly gave it to a female ICE agent. They both laughed. Knutson told me he had never been a protester. It seemed pointless, or just a way for people to expiate their sense of guilt. But when he saw those ICE agents laughing, something broke inside him. ‘I grab my keys, I grab a coat, and drive over,’ Knutson told me. ‘I barely park my car and I’m running out screaming and crying, “You stole a fucking flower from a dead woman. Like, are any of you human anymore?”’”

“Again and again,” Robert F. Worth writes, “I heard people say they were not protesters but protectors—of their communities, of their values, of the Constitution.” Worth, the former Beirut bureau chief of The New York Times, sees similarities between the people on the streets of Minneapolis and the pro-democracy movement in Cairo in 2011. They’re not protesters by vocation, but volunteers who are coordinating with one another to protect the communities they live in. Thousands have gotten legal observer training so that they can monitor ICE operations in an appropriate way. They stand watch outside schools and daycares in sub-zero temperatures to make sure kids arrive safely. They’re not anti-government activists, but—as Hamilton Nolan wrote in a recent dispatch from the city—simply “regular people, decent people, faced with intolerable things.”

Steven Levitsky, Lucan A. Way, and Daniel Ziblatt, “The Price of American Authoritarianism” (Foreign Affairs)

“In Trump’s second term, the United States has descended into competitive authoritarianism—a system in which parties compete in elections but incumbents routinely abuse their power to punish critics and tilt the playing field against their opposition. Competitive authoritarian regimes emerged in the early twenty-first century in Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s Turkey, Viktor Orban’s Hungary, and Narendra Modi’s India. Not only did the United States follow a similar path under Trump in 2025, but its authoritarian turn was faster and farther-reaching, than those that occurred in the first year of these other regimes.”

One point I’ve been trying to make is it’s not just my opinion that democracy in the US is in trouble. That’s hard for Americans to accept; we think of ourselves as the historical standard-bearers for democracy. But the broad consensus among political scientists is that the US is slipping into authoritarianism. Bright Line Watch’s latest survey finds democracy experts generally think the US is closer to “a mixed or illiberal democracy than a full democracy.” Some of the most prominent—the ones grad students need to know to pass their comparative politics exams—are sounding the alarm. Larry Diamond, who was a founding editor of the Journal of Democracy, wrote last February—in an essay I shared with subscribers—that the US is in “a free fall” to tyranny. Steven Levitsky, who with Daniel Ziblatt wrote the book on How Democracies Die, told NPR in April that “we are no longer living in a liberal democracy.” Around the same time, Lucan Way—he and Levitsky coined the term “competitive authoritarianism” in a 2002 paper2—told me the US has descended into competitive authoritarianism. In an essay in Foreign Affairs, Levitsky, Way, and Ziblatt write that while the US has engaged in undemocratic behavior before, the Trump administration’s authoritarian actions have no precedent in recent US history. But Levitsky, Way, and Ziblatt nevertheless stress that competitive authoritarian regimes are still competitive; authoritarians can still lose. Indeed, I believe Trump would lose an election held today in spite of everything he could do to try to rig it in his own favor. So we cannot accept the end of American democracy as a fait accompli. “The outcome of this struggle remains open,” they write. “It will turn less on the strength of the authoritarian government than on whether enough citizens act as though their efforts matter—because, for now, they still do.”

This country was founded on a decisive rejection of imperial authority. We’ve always been at our best when we’ve championed a multilateral, democratic order open to everyone. We’ve likewise always been at our strongest when we’ve fostered dissent and demanded the government be accountable to us. Minneapolis is a shocking test case—a kind of proof of authoritarian concept—intended to establish the principle that the Trump administration can act and even kill with impunity. But we can still protect our democracy and hold the administration accountable. It would be un-American not to.

Thank you for reading Telling the Future. Related posts include “It Can Happen Here,” “Rhinocéros,” “Politics Is Interested in You,” and “American Totalitarianism.” If you enjoyed this, please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber.

Well said, Robert

Heart-breaking, but true. Any ideas/suggestions on how someone NOT in Minnesota can help?