We Always Throw the Bums Out Eventually

I'm already ready for another change tbh

Trump benefitted from a global wave of anti-incumbent sentiment in 2024. The good news for Democrats is that they’ll be the ones who benefit from voter dissatisfaction next in the next election.

“Disappointment,” Arthur Schlesinger wrote in The Cycles of American History, “is the universal modern malady.”1 We’re never satisfied with any government or policy but always focus instead on all the problems that remain. Our expectations continually adapt to whatever progress we make, so that we’re on a kind of hedonic treadmill. Our restless dissatisfaction means, as Schlesinger said, that '“it always becomes after a while ‘time for a change.’”

Because voters are never happy for long with any direction we take, electoral politics functions like a thermostat. When it gets too hot or too cold, feedback mechanisms in a thermostat push the temperature back toward its nominal set point. Similarly, when democracies move one way or another, elections generally push them back the other way. Public opinion tends to move in the opposite direction of policy; voters reliably become more conservative under Democratic presidents and more liberal under Republican presidents. That’s why when the party out of power wins an election, it doesn’t necessarily mean the country is undergoing some permanent political realignment. In most cases, voters have simply and predictably turned against the incumbent status quo.

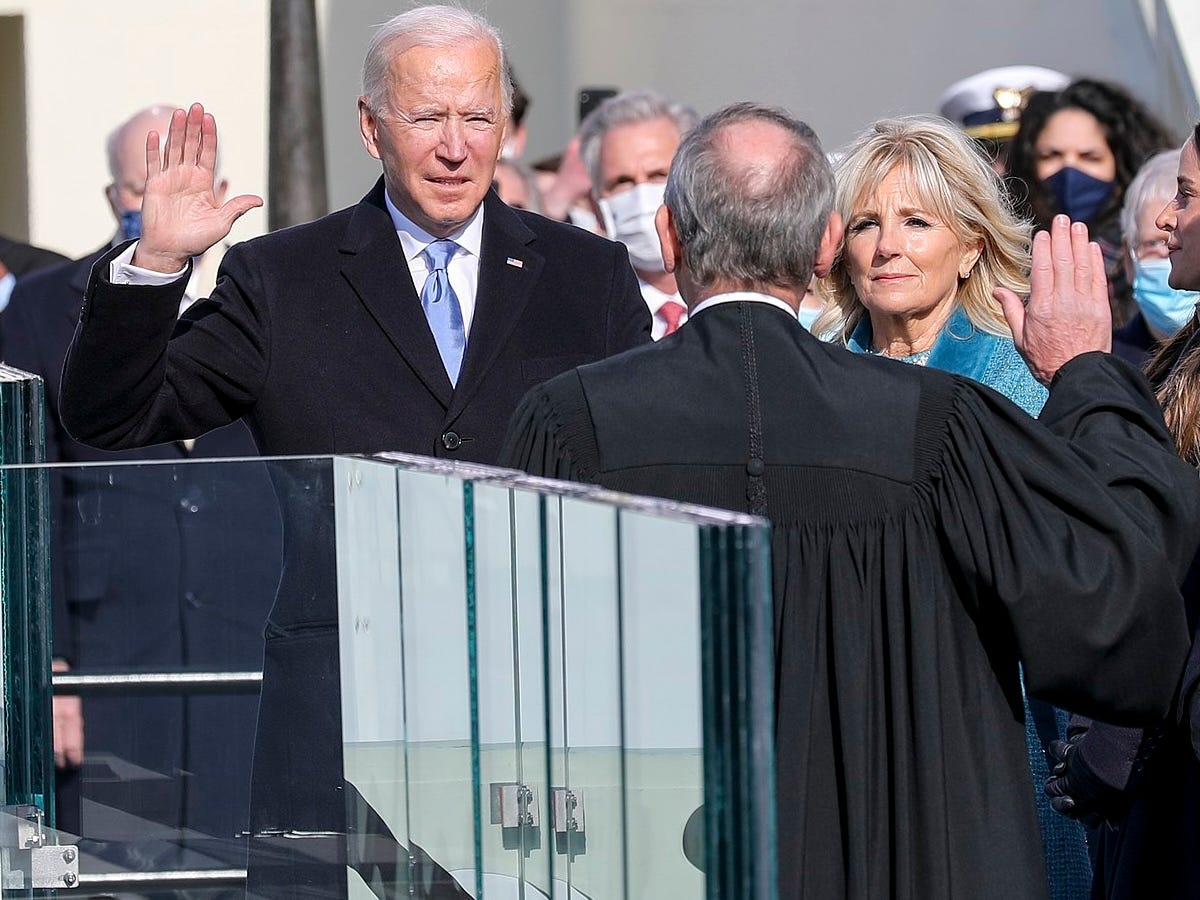

Voters turned even more sharply and quickly against incumbents in recent years in apparent anger at post-COVID price increases that were largely beyond the control of governments. In normal circumstances, incumbent politicians have an advantage that initially helps them survive as voters start to sour on their policies. But in 2024 voters turned incumbent parties out in election after election around the world. How well incumbent governments performed relative to their peers didn’t seem to make much difference. There are always things a candidate could have done differently—and Democrats will need to develop a more compelling message with the old liberal consensus breaking down—but I remain convinced that there isn’t much Kamala Harris could have done to weather voters’ intense reaction to the last few difficult years. Democrats were probably doomed the moment Joe Biden took over a country still recovering from the pandemic.

We should always seek to improve our condition. I wish we had a better way of assessing policy than kneejerk anti-incumbency—and I’d personally prefer our ideological set point were further to the left—because the status quo isn’t always worse than the alternative. But the advantage of thermostatic politics is that it keeps us from veering off into extremes for long. The US remains closely divided. Although Donald Trump’s victory was decisive in some ways—he swept the swing states and improved on his previous performance almost across the board—he still won less than 50% of the national popular vote. Trump himself lost fairly handily in 2020 but still managed to win this year without significantly changing his strategy. Democrats are likely to rebound too when voters inevitably grow dissatisfied with the Trump administration. As Derek Thompson wrote in The Atlantic, “Democrats have been temporarily banished to the wilderness by a counterrevolution, but if the trends of the 21st century hold, then the very anti-incumbent mechanisms that brought them defeat this year will eventually bring them back to power.”

That is, of course, as long as Republicans honor the results of the future presidential elections. Elections are the main feedback mechanism that keeps our government running at a tolerable temperature. Democrats were glad we could vote an incumbent out of power in 2020 when Trump was in office; Republicans are glad we can vote one out now that Biden is. But Trump would like to disable that mechanism. He has made it clear again and again that he will only accept results that go his way and has even expressed regrets about leaving the White House after losing the election in 2020. He’s now in the process of stocking his new administration with people who would have supported his attempt to hold onto power illegitimately. While the 22nd Amendment bars him from a third term as President, he has already begun floating the possibility of staying in office past 2028. It’s frankly hard for me to imagine Trump ever leaving office willingly. If Trump stayed in office past the end of his term it would break the fundamental compact of democracy that no victory is permanent and no loss is final; when we are disappointed with our leaders, we can always demand a change.

Thanks for reading Telling the Future! This newsletter depends entirely on reader support, so if you find it interesting or valuable, please consider supporting me with a paid subscription. Also, if you enjoyed this post, you can share it with others using the button below.

I normally interpret fellow forecasters very literally, but I won't do so for your: "It’s frankly hard for me to imagine Trump ever leaving office willingly." Surely the most likely scenario is that in 2028 we have another election and Trump doesn't run. Then he is replaced on schedule by the winner.